We’ve come to the end of my LLM app series (for now). I really enjoyed putting this together and I will be working in the coming weeks on expanding some of these sections. I’m looking ahead to my tutorial at ODSC, where I’ll be covering these and other topics. The materials will be made available as I put them together, so keep an eye on this blog and this repo for that!

I figured it might make sense to review some of the things I’ve covered in the series (looking back). Then, I provide some thoughts on what’s coming up for the field (looking ahead). And finally, a set of resources I use to keep up to date.

Simple LLM applications

Here, I set up the framework of a basic conversational LLM application:

- Frontend - Similar to any other application

- Input processor - Translate the user interaction into model input

- Model - In this case, the LLM itself or whatever service is hosting the LLM (e.g. OpenAI)

- Memory - Context storage

- Output processor - From model to user

In the application section, I set up some simple examples using Huggingface’s transformers library. I coded things from scratch here without much attention to providing an attractive or functional interface. So in the next post, I aimed to abstract a bit:

Ollama, LlamaBot and Oobabooga

I reviewed three tools, each offering something different in terms of interface and functionality.

Ollama

Ollama takes the best of the open source optimization technologies (e.g. llama.cpp) and wraps it all in a nice little application. At the expense of customizability, you essentially get the full conversational stack outlined above.

Example notebook using LangChain with Ollama

Oobabooga

Oobabooga wraps technologies like transformers, Gradio and peft into one neat little package. That means things like UI, model retraining and processing pipelines are all built in. New additions are continuously being developed because open source is great.

For a working example, check out this notebook by the maintainers.

LlamaBot

This project interested me when I first looked at it because the goal was to make interactions with LLMs more “pythonic”. This notebook walks through an example use of the library.

RAGs to riches

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) comes from a process of enhancing input into an LLM with relevant information (e.g. web search results). This approach reduces the chance the LLM will “make up” (hallucinate) facts and enables it to stay up to date.

A working example is available here.

LLM fine-tuning

This was a two-parter as it ended up being a larger topic than I could just cover in one post.

Supervised Fine-Tuning

In the first post, I experimented with Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) using OpenAI’s APIs. SFT can be understood as when a model is fine-tuned on input/output pairs. Compare this to fine-tuning the model by having it predict the next word given the context.

This notebook has an example implementation in which I try to make GPT 3.5 talk more like a Friends character.

Language fine-tuning

Here, I experiment with fine-tuning with next word prediction. Much of this post focuses on strategies (quantization and Low-Rank Adapters) for tweaking the output of an LLM without having to adjust a massive number of high-precision parameters. In the Kaggle notebook example, I walk through how to implement these approaches in free GPU hardware made available from Kaggle.

Again, the goal here was to make the model talk more like a Friends character. In both cases, we saw changes to the output, but not necessarily useful ones. In general, the model did learn to change its tone, but it didn’t end up being the funny, friendly assistant we were hoping for.

LLM agents

In the final part of the series, I zoom back up to the application level. There’s a lot of exciting developments happening with incorporating LLMs into multi-functional systems. These systems, broadly, as referred to as “agents”. This is a reference to reinforcement learning where components of the system can interact with an environment and adjust their subsequent interactions based on the results of those actions.

The key components of these systems are:

- Planning - Plans and verifies the steps towards resolving a tasjk

- Memory - Stores the “state” of the conversation, steps processed, etc.

- Tools - The capabilities that the LLM can use (e.g. calculator, web search)

I walk through an approach to building an agent that can query and return local events in this notebook.

What’s next?

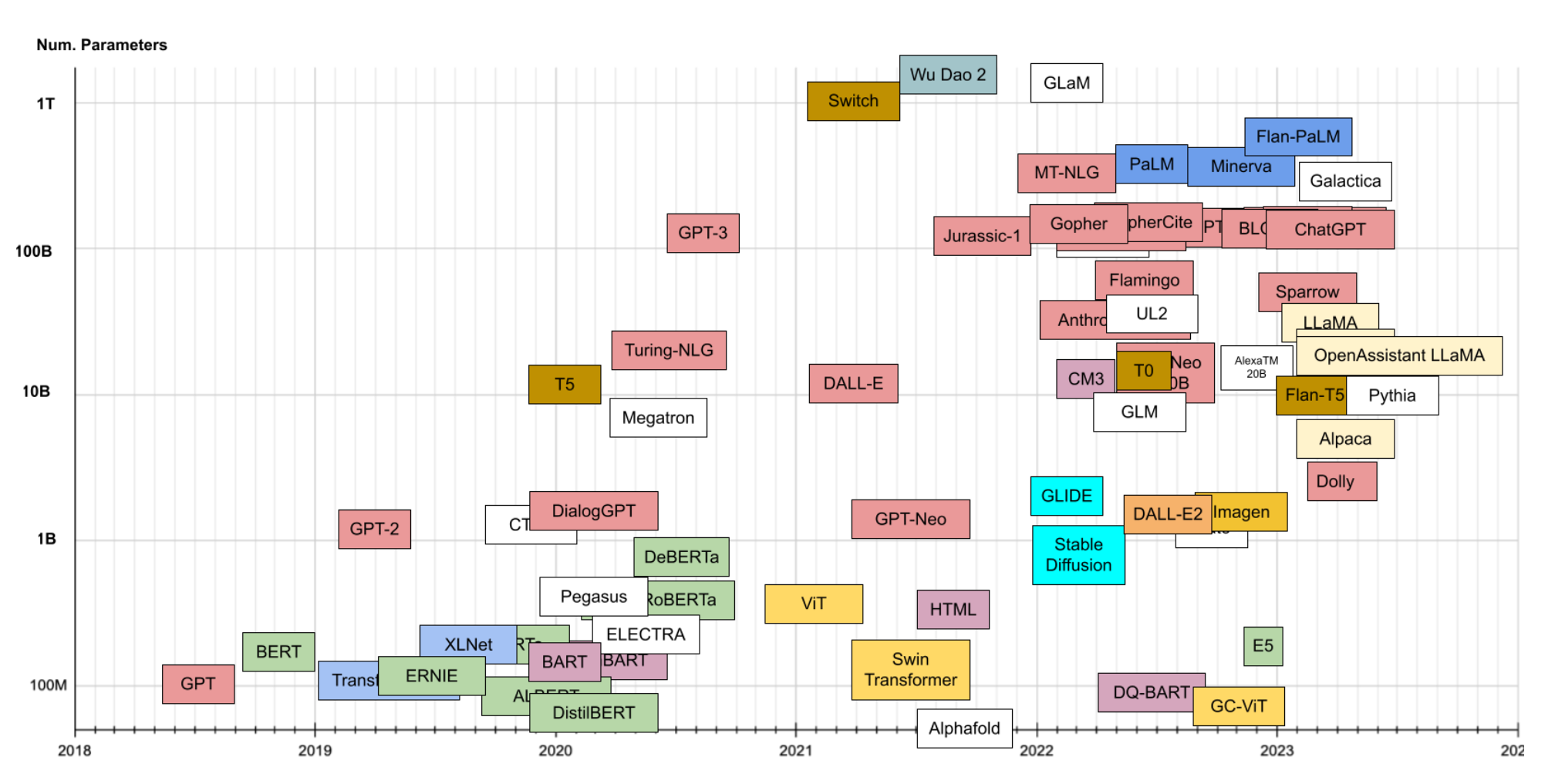

The pace of development in LLM technology has been absolutely unprecedented. I referenced this diagram back in the olden times of 2023, and it is already wildly out of date:

So you might be asking where the field is going and how it is possible to stay up to speed. To be honest, the moment I publish this it’s likely to be out of date. But here’s where I see things going:

Flexible LLM application systems

As pointed out in the LLM agents post, LLM applications can be brittle due to the inherent variability in how an LLM responds to input. In my opinion, relying on a particular structure to be output by these models is not realistic, as stochasticity is built into their designs. To that end, I think systems that use these models will need to be designed flexibly to accommodate these variations.

One really interesting library seeming to come into that space is DSPy, which describes itself as “Programming—not prompting—Foundation Models”. Rather than spending time with extensive prompt engineering, the prompts are optimized based on their performance against a particular metric. This can also include fine-tuning the model itself. The goal, as I understand it, is to better establish LLMs as a component in a pipeline; fitting both support architecture and the model itself to the use-case.

LLM development frameworks

While we mostly experimented with LangChain in this series, there has been a proliferation of tools for developing full-stack LLM applications. The “stack” in this case is the model I’ve referred to throughout this series:

- Frontend - Similar to any other application

- Input processor - Translate the user interaction into model input

- Model - In this case, the LLM itself or whatever service is hosting the LLM (e.g. OpenAI)

- Output processor - From model to user

As mentioned above, Oobabooga provides an open-source toolkit with a wide array of functionality. LlamaIndex has an open-source package focused on retrieval pipelines, but offers additional managed services. This is similar to other libraries like Helicone which has an open-source observability library and a set of managed services to mix in.

On the closed-source side: Roli provides an interesting tool set for designing and deploying LLM workflows. The idea here is that you may have multiple models in multiple workflows and Roli provides tools specifically designed to help put those together.

Of course there’s also the major players, Google with its Vertex AI, Amazon with Bedrock and Microsoft is currently spinning up its Azure AI studio.

This is by no means comprehensive. This is an active area and, like I said, probably there’s some new hot shot that’ll announce as soon as I post this.

Bigger, longer and multi-modal

I’ve made this point before but models have just been getting bigger. GPT-4 is rumored to have 1.8 trillion parameters. They’ve also been getting longer (in terms of context window). GPT-4 Turbo can accomodate 128k tokens, 32x larger than GPT-3.5 Turbo Instruct’s 4k tokens. Google claims Gemini 1.5 is up to 1 million tokens.

One thing I haven’t really dug into in this series is the explosion in research on multi-modal models. That’s because, honestly, I need to sleep at some point. A “mode” in this context is a type of data like language or video. A multi-modal model is capable of processing one or more of these modes. GPT-4 and Gemini can handle text and images. I remain a bit confused why these are being called LLMs, since they’re not just Language Models anymore. Large Multi-Modal (LMM) sounds better to me.

Smaller, cheaper and open-source

There’s another branch of LLM development that has been asking the immortal question “does size matter?” The answer, it seems, is not too much. I dug into that a bit with discussions on quantization and parameter-efficient fine-tuning, but some efforts take this to the next level.

Where we were messing around in 8-bit quantization, Microsoft is out here proposing a 1-bit LLM. This means dramatic reductions in memory footprint and faster inference. A recent paper by Ma et. al. (2024) reports that their 70B(illion) parameter 1.58-bit model is more efficient than a 13B 16-bit model. That’s big. Or, I guess, small.

Another trend I’ve been seeing is open-source and open-weight1 models catching up to closed-source models. Models by CausalML perform comparably to GPT-4 on several MT-Bench domains and GPT 3.5 has been surpassed by open models for code generation and chatbot performance.

There are open source replications for just about every new model released by the big players. One of the big announcements of this year was OpenAI’s Text-to-Video model Sora. This came in mid-February and within a week, there was alread an open source replication on the way.

Yann LeCun has suggested that open development of AI is the ONLY way forward.2 His reasoning is that these models are only as good as the data they use. If the models can promise open access, people will be more willing to share their data with them.

How do I keep up?

I’ve been in a desperate race to keep up with the pace of the field. I have had…limited success. But even that is thanks to the incredible efforts of some folks generating detailed, up-to-date content. Here are some sources I rely on:

- DAIR’s papers of the week

- Lillian Weng (OpenAI)

- Sebastian Raschka (Lighting.AI)

- Sebastian Ruder (Cohere)

- Awesome LLM resources

- Awesome series generally is pretty great

- This Week in Machine Learning (TWiML)

-

I differentiate between open-source and open-weight because…they are different. Open source means something very specific. Llama, Mistral, Falcon and others DO NOT meet this standard. BLOOMZ, dolly amd Open Assistant are examples of open source models. More info here ↩

-

I do wonder, though, how he feels about Llama’s restricted license. ↩

Ben

Ben

LLM Apps Part 6 - Call my LLM agent!

LLM Apps Part 6 - Call my LLM agent!