We’ve explored how to make our LLM applications conversational, relevant and personalized, but now it’s time to put them to work.

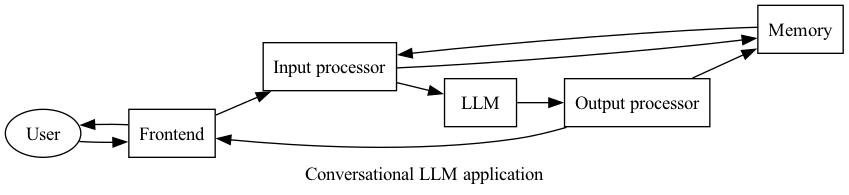

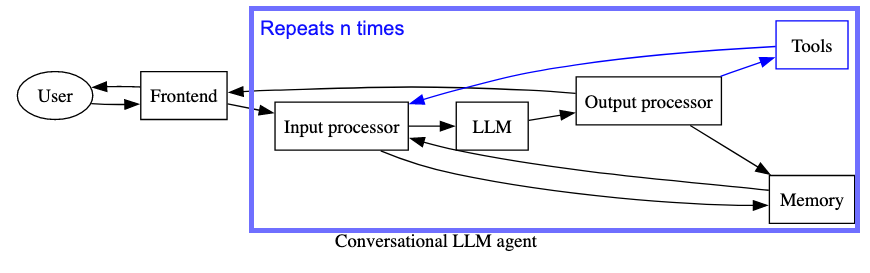

This is the final applied part of my LLM app series. We’ve been building off this structural model for conversational LLM applications:

- Frontend - Similar to any other application

- Input processor - Translate the user interaction into model input

- Model - In this case, the LLM itself or whatever service is hosting the LLM (e.g. OpenAI)

- Memory - Context storage

- Output processor - From model to user

In part 4 and 5 of the series, we were focused on tuning the model itself. But today we step back out and look at the whole system. What if we want more than a conversation about Alpacas and how we feel about Ross from Friends? What if we want our LLM to tell us about cool things happening in our area? What if we want our LLMs…to use tools?

Not so secret agents

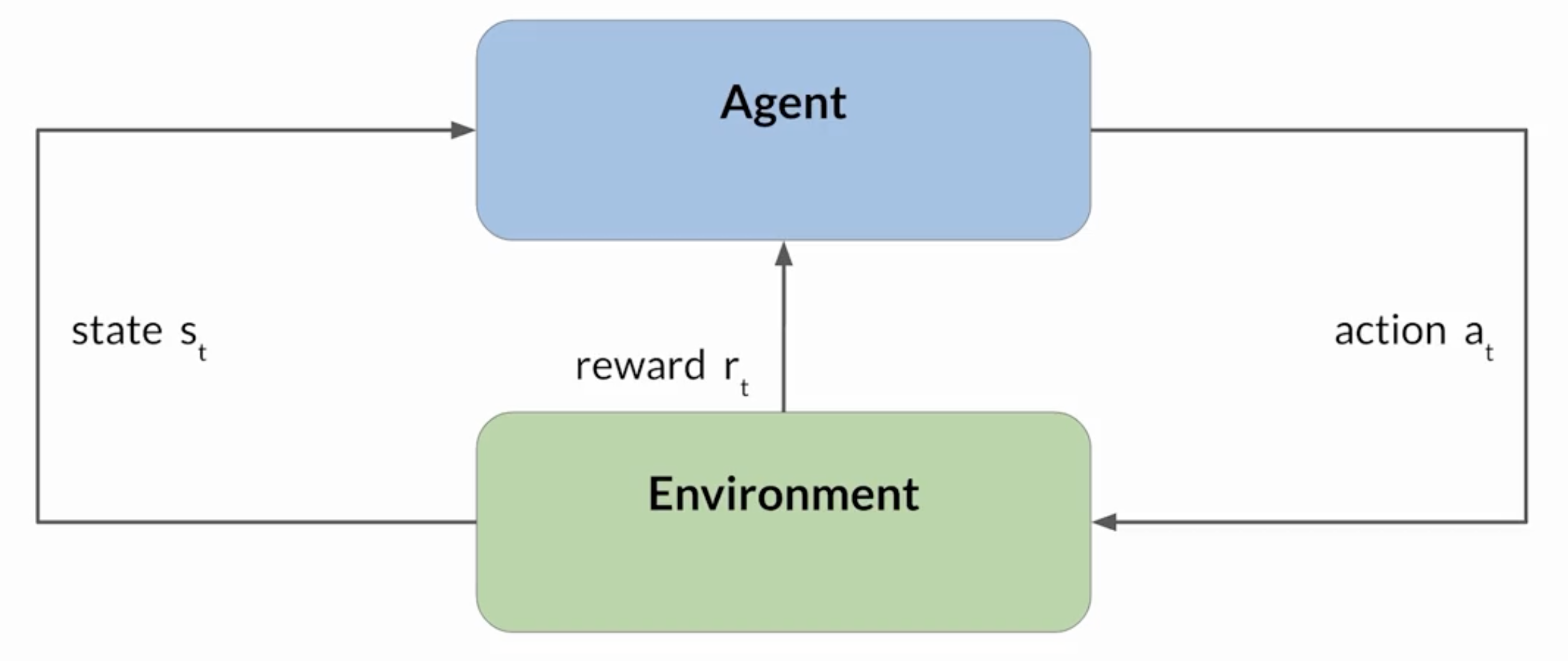

If you’ve been listening to talk about AI lately, probably you’ve already heard the term AI agents. For me, when I hear “agent” I think of Reinforcement Learning (RL). In these systems, an agent takes actions within an environment, which provides the agent with rewards/penalties. The agent receives that feedback and “adapts” its strategy in order to maximize the reward. From the DeepLearning.AI+AWS course on LLMs:

This was all the rage back when RL systems were beating Mario, dota and…maybe taking over the world?

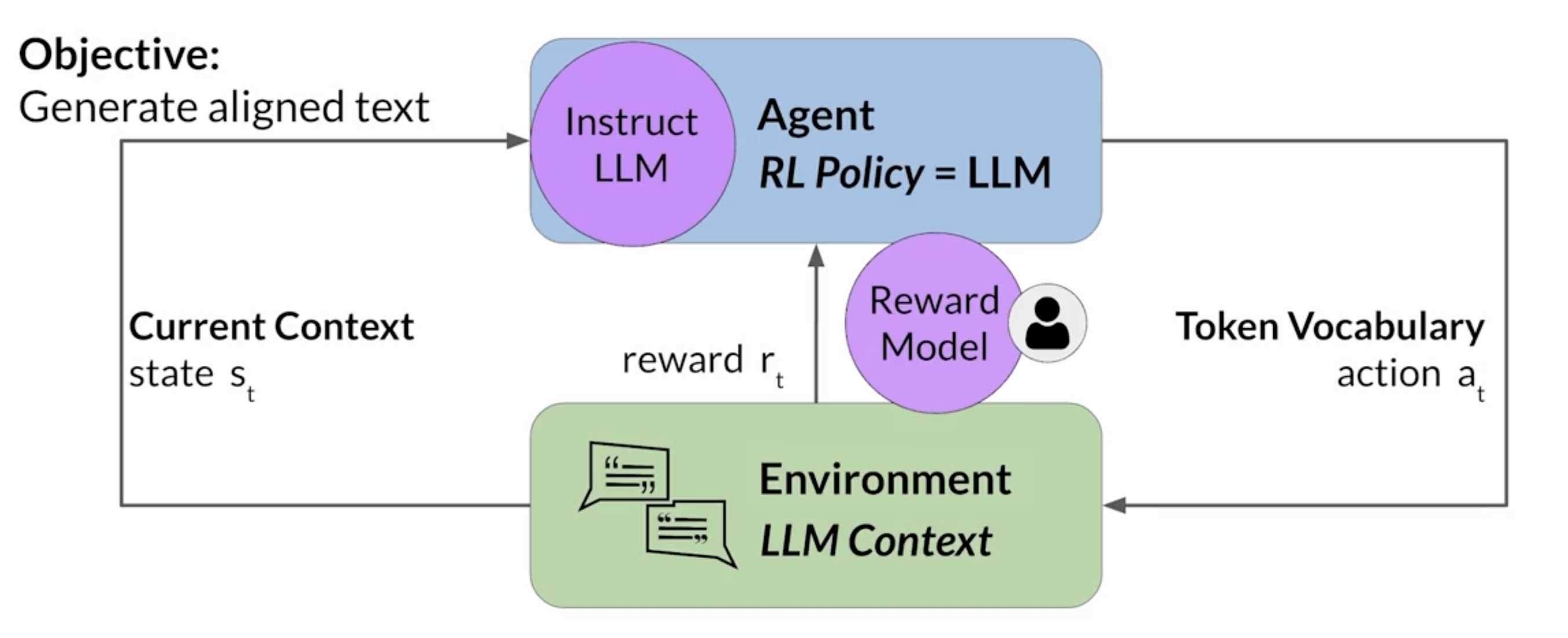

There’s been a recent drawing together of the fields of RL and NLP with the popularization of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). I touched on this in a previous post. In RLHF, the agent is an LLM and its action space is the tokens it can generate. A nice illustration of this:

Typically, when people talk about LLMs as agents, they’re focused on their ability to do complex tasks like designing chemicals Wikipedia articles or beating Minecraft. In the RLHF diagram above, we see the LLM agent’s action space consists of the tokens it can generate. That’s fine if the task requires generating text, but what about conducting a web search or even looking up today’s date? In the words of a colleague of mine, the language is the “glue” connecting the system’s components. The LLM specifies the tools to use, how to use them and then uses their output to generate a useful response.

An LLM agent typically contains the following components:

- Planning - Plans and verifies the steps towards resolving a task

- Memory - Stores the “state” of the conversation, steps processed, etc.

- Tools - The capabilities that the LLM can use (e.g. calculator, web search)

It makes sense to dive a bit deeper into each of these.

Planning This is something we, as fully autonomous agents, do really well. Think of the following word problem:

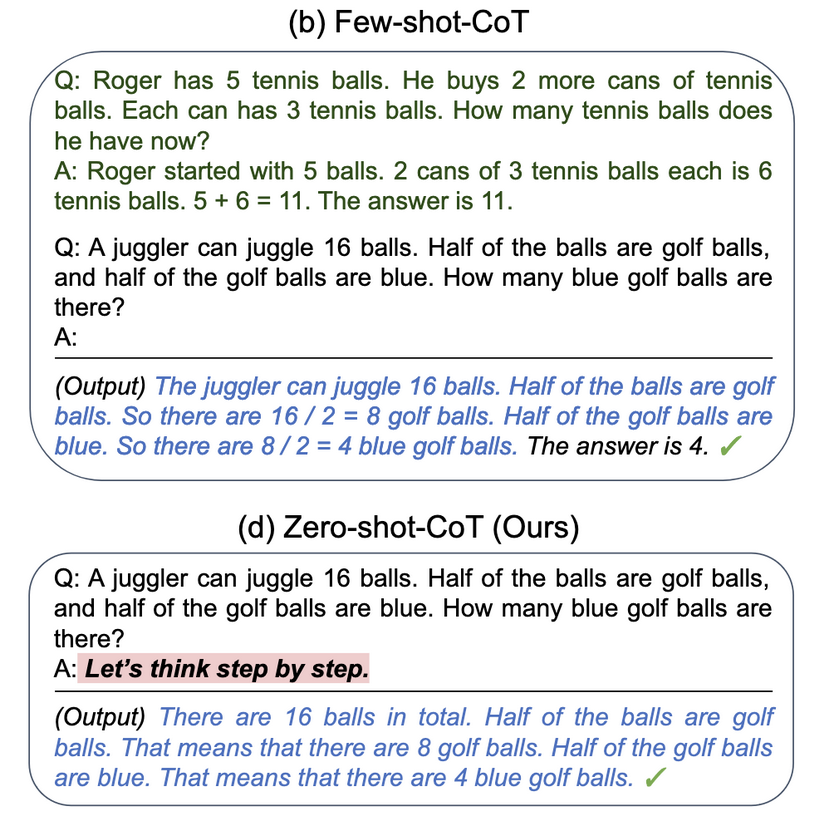

A juggler can juggle 16 balls. Half the balls are golf balls and half of the golf balls are blue. How many blue golf balls are there?

This may not be exactly your process, but you understand this can be calculated as a two step process:

- Number of golf balls: 16/2 = 8

- Number of blue golf balls: 8/2 = 4

This example may look familiar if you read my post on in context learning. Just by directing a model to “think step by step”, you end up with a similar breakdown in steps. And, as a result, the model is able to answer it correctly:

Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting is a very basic version of a planning component. The model is prompted to break down the input into a series of steps. Since generation is conditional on what has been generated so far, the fact that all the necessary information has been outlined, it is more likely to generate a correct reply. This can get kind of ridiculous but it does seem to work.

You could see how this “planning” process can get much more complex. The model could be prompted to ask itself follow-up questions and even review its answers to make sure they make sense. We’ll examine one example of these more complex flows called Reason and Action (ReAct) in the code example.

Memory To some extent we’ve covered this in a previous post. An LLM’s “memory” contains the history of input and output. In this context, the memory may also contain the steps the model has taken so far to accomplish the task. Potentially it can include any errors the process ran into, allowing the model to correct itself in the follow-up steps.

Tools

As mentioned above, an LLM just generates language, it can’t actually use a tool itself. It can, however, specify the tool to be used and how it should be used. Just like you might read a manual and understand how to use the tool, the LLM can “understand” natural language descriptions of a particular tool. So if you have a python function today that provides today’s date, you might write it with a docstring like so:

from datetime import date

def today(text: str) -> str:

"""Returns today's date, use this for any \

questions related to knowing today's date."""

return str(date.today())

Then, if a user asks:

What day is it today?

Given that the LLM has been provided with the function, its description and its usage, it might break this task into steps. It might first generate:

The user wants to know today’s date. I need to use the function: today()

Part of the agent system would be some method of parsing this output and executing any specified tools (e.g. a connected python interpreter). The result of this process would be passed back to the LLM, which would generate a new response based on the context. In this case, the today function would return “2024-02-26” and the model would be able to answer the question for the user:

Today is February 26th, 2024.

We’ll walk through an example later. But suffice to say that so long as the LLM “knows” what tools it has and how to use them, it can generate parseable specifications which can then be executed. I feel like this “parser” is important to call out - mainly because it has to be built to be robust to the variability inherent in language generation.

One additional note - the “retriever” part of the RAG workflow we walked through could be considered a tool. In that post, the workflow was designed around the retriever. By the definition we’re setting up here, the LLM needs to be able to specify when and how to use a tool to be considered an agent. But it’s fuzzy where the boundaries are here.

Less words, more pictures

As described above and throughout this series, I’ve hung my hat to the following conversational LLM application model:

One of the reasons I pulled out these “processor” components is because of workflows like this one. The agent structure mainly means incorporating the ability for the model to consider tools in its generation process:

Explained in words:

- Frontend - Unchanged; how the user interacts with the LLM

- Input processor - Combine user input with planning guidance, tool information and context

- This step may be repeated

ntimes with multiple calls to the LLM (e.g. output from a tool use)

- This step may be repeated

- Model - Unchanged, though more complex flows might involve using different LLMs for different steps

- Memory - May now include input/output not specifically from the user (e.g. to/from a tool use)

- Output processor - From model back to itself (self-ask), to a tool or (at the end) back to the user

- Again - repeated

ntimes as needed

- Again - repeated

Now, this model doesn’t cover everything. You’ll notice I’m leaving out “planning” here. My thought is that so long as the planning structure is part of the prompt, it gets encompassed in the engineering happening in the “input processor”.

I encourage you to look at some other diagrams that are specifically focused on the agents. These are also great sources for more information:

Enough talk! Let’s code.

Call my agent!

This example comes from my kind of wacky ODSC talk idea to create an LLM “friend”. I want to give it the ability to invite me to cool events, making it immediately more useful than my actual friends. To do that, I’m going to equip it with a tool that enables it to look up local events on Boston Calendar and then suggest suggest some to me.

So that fits into our model like this:

- Frontend - Jupyter/Collab notebook

- Input processor - Prompt template for Reason+Act (ReAct) agent

- Also incorporates memory as different steps of the workflow are executed

- Model - GPT 3.5 via OpenAI API

- Memory - Expanded throughout the workflow

- Output processor - Parser for identifying whether and how a tool needs to be used

For this, I’ll be using LangChain and the OpenAI API with GPT 3.5. So if you’d like to follow along, you’ll need to obtain your own OpenAI API token. You can see the notebook for implementation here.

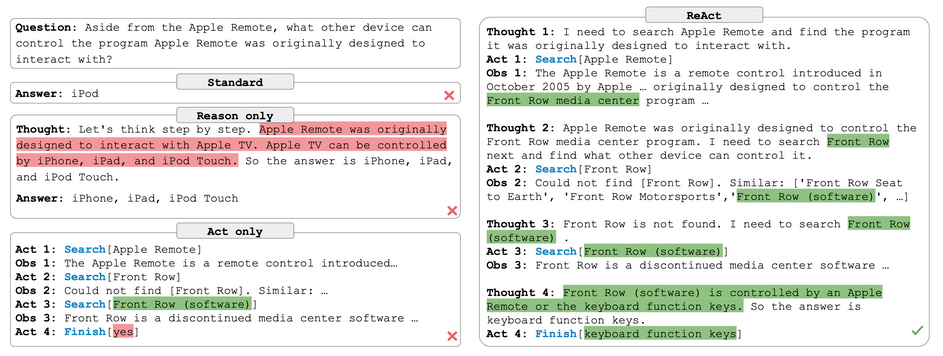

First, you’ll see that I have a pretty elaborate prompt set up here. This is taken from LangChain’s ReAct agent example. ReAct is shorthand for Reason + Act and comes from a 2023 paper by Princeton and Google researchers. This visual from the paper captures the flow:

In this - “reasoning” is essentially just how the model breaks down the problem when prompted to think step by step. “Act” is the model specifying the functions to be executed and their input parameters. Independently, they yield incorrect answers, but combined, they manage a multi-step process yielding the correct answer.

The prompt I use gives the model a template for its answer and includes placeholders for LangChain to insert parameters like the input prompt and the tools available to the agent. The agent_scratchpad is where the agent’s process (the context) will be inserted.

The tools themselves are just functions that have descriptive docstrings so the model can understand, in natural language, what they do. To enable LangChain to insert them properly in the prompt, you need to use the tool decorator.

Setting up the agent is fairly straightforward, thanks to the hard work by the LangChain team. We create a ReAct agent that has the components for parsing output and executing functions. The documentation gives more detail, but at a high level, it will format our prompt, process the output to identify what functions (if any) need to be run, run those functions and then pass their output back to the model for next steps.

In the first example, we’re giving the model information about the today() function in order to have it be able to answer a question about the date. In response to the input query “What day is it today”, it replies in the format we specified:

We can use the “today” tool to find out today’s date. Action: today Action Input:

In this case, the input to the today function is an empty string. The parser (built in to the ReAct agent flow) extracts these elements, calls the today() function and returns today’s date. The flow thus far is passed back into the model, which outputs its final answer

Today is February 26, 2024. Final Answer: February 26, 2024

The agent flow identifies that the model has output a final answer and doesn’t run another iteration through the model.

The more complex workflow I want to design is an agent that can look up local events and suggest them to me. That means a few steps:

1) Identify the time period of interest 2) Pull event information from the internet (in this case, Boston Calendar) 3) Format that information for output

Much of the get_events function is dedicated to scraping and processing Boston Calendar. You’ll notice I just sample 3 random events. Likely it would be more interesting to compare these events to what my usual interests are, but I wanted to keep it simple for now. The get_events function requires a date or a weekend “number” (oddity of Boston Calendar itself). It’s up to the model to get that information using the today or weekend functions.

I try a couple formulations to test out the workflow, asking the agent what’s going on today, this weekend or even a few days from now. For the most part it handles these requests pretty well. I experimented with a few ways to make it output the result more in the style of the “friend” we designed in a previous post, but it tended to be less informative than the default style.

You’ll notice certain things don’t work, like asking it what’s going on tomorrow. It doesn’t seem to understand that it needs to add one to the current date, or at least not consistently. This is kind of the issue I’ve seen with my experiments. The workflow is fairly brittle. This blog post attempts a much more complex workflow and has to present the model with some pretty detailed instructions to make it work. And she’s using GPT-4. And she still finds it unreliable. That brings me to something I want to note here.

What happened to Llama-2?

You might be asking why I don’t have an open-source implementation. Llama 2 7B seems to be good at a lot of things, but it doesn’t make a great agent. The prompt for the ReAct workflow is pretty complex. These smaller models tend to fall apart under that kind of pressure.

Not at all to say that open-source models can’t do this! It’s been done with the 13B parameter version and Mixtral 8x7B outperforms GPT3.5 on some tasks. (Note - Mixtral 8x7B is effectively 42B parameters…but it is on Ollama!)

But can you hand all your customers off to your LangChain agent? Um, probably not.

Agents in the spotlight

I realized all my kvetching about brittleness and the simplicity of this example implementation might lead to you believe agents aren’t all that impressive. So I’d like to round out this post with a couple pretty incredible examples of LLM-powered agents.

Voyager answers one of the most pressing questions of our time; can AI beat Minecraft?

The answer, it seems like, is yes! Minecraft poses a particularly difficult challenge since beating the game requires a series of complex actions, each with their own material components that can only be obtained through purposeful exploration of the game environment.

Rather than building on monolithic “solver” model, the developers assembled a system around three main components: 1) Automated curriculum - A task list where each step builds on the others (e.g. mine diamond before crafting a diamond sword) 2) Skill library - Storage of code blocks to do different tasks (e.g. mine diamond) 3) Iterative Prompting Mechanism - Manages the flow between components, updating the curriculum state and generating executable code through interaction with the library

This whole system is built on top of some carefully designed prompts and customized workflows, but there is no explicit fine-tuning happening here. The model just knows it has a set of tasks to do and can understand when its actions have made progress and when they have failed.

ChatDev takes things to the next level by having a “community” of agents interacting with one another. Each agent has a particular “role”, which means they have particular tasks they can execute and tools to which they have access. The product of one agent can then be interacted with by another agent and so on. What’s really amazing here is that there are workflows around “collaboration”. That means one agent may check another’s work, provide feedback and then that feedback can be incorporated in the next iteration.

The result? These communities can actually develop things like a website or a simple game!

Both of these examples are pretty neat experiments and I’m excited to see what comes next here. I have been looking for real-world examples of agents in action, but so far a lot of this still seems like it’s in the research stage. I welcome any examples you’ve encountered that you want to share!

Ending thoughts

Let’s sum up what we’ve covered here:

- LLM agents are made up of several components: Planning, memory and tools

- These components allow the LLM to answer complex requests with multi-hop workflows

- Using LangChain and GPT3.5 we were able to implement a simple workflow for recommending local events

- These agents can do very impressive things, but they require carefully engineered prompts and support systems (e.g. parsers)

I think this is a really interesting area, but I still think there is a lot of work that needs to be done to make these reliable enough for the real world. In general, even specialized LLM workflows have a lot ways they can go wrong. Creating a generalized LLM workflow seems, to me, trading a lot of reliability and transparency for potentially more flexibility.

In my next post, I’ll sum up everything I covered in this series and give some more detailed closing notes. Thanks for reading!

Ben

Ben

Insight Lane at MIT

Insight Lane at MIT