In this post, we explore how to make our LLM application to “talk” the way we want by fine-tuning OpenAI’s GPT3.5 model.

This is part 4 of my LLM app series. It pairs well with part 5 where I dig deeper into the topic.

Again, let’s start with our LLM framework:

- Frontend - The user interface, as with other applications

- Input processor - Translate the user interaction into model input

- Model - In this case, the LLM itself or whatever service is hosting the LLM (e.g. OpenAI)

- Memory - Context storage

- Output processor - From model to user

In this post, we’re focused on the model itself. We’ve been using Llama 2 mostly in our examples with Ollama. In my Intro to LLMs series, I explained how models like Llama are the product of a couple “iterations” of training:

- The model is trained on a general text corpus to predict the next word (Pre-training)

- The model is trained on input/output pairs (SFT/RLHF)

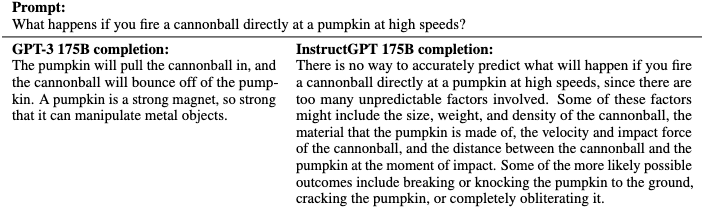

I describe these in detail in part 3 of my LLM series. The difference between a model that is only pre-trained versus one that gets pretraining and SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning) is stark:

In this case, fine-tuning involved giving the model input/output pairs and tuning the model to produce the output (via next-word prediction).

The label “fine-tuning” is applied to basically any time you take a model that has already been trained and further train it on something new or different. The key is that fine-tuning involves the model changing in some way based on the fine-tuning dataset.

The version of Llama 2 we’ve used in Ollama so far is the Llama 2-chat model, which has already gone through instruction and alignment tuning. As a result, it makes a pretty useful assistant.

So if it ain’t broke, why tune it, right?

Well, typically these models are trained on large piles of web text (e.g. CommonCrawl).1 This is great for general knowledge (given from a particular perspective), but when we get to specialized knowledge or language, it breaks down.

Think of coding assistants as an example. This is maybe one of the most popular applications of LLMs. I asked Llama 2 to give me code for a simple bar chart in Python and it provided the following code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Data for the bar plot

values = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

# Create the figure and axis

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Plot the data as bars

ax.bar(values)

# Add a title and labels

ax.set_title('Bar Plot Example')

ax.set_xlabel('Values')

ax.set_ylabel('Bars')

# Show the plot

plt.show()

This looks like complete code, but it doesn’t actually work due to the syntax of the bar plot (it requires two parameters for the x and y axes). You’ll see all kinds of errors like this, especially with the smaller Llama model.

Enter codellama, which is also available on Ollama. This model is initialized from the same 7B-size Llama 2 model and then fine-tuned on code.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Data for the plot

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Create the plot

plt.bar(range(len(data)), data)

# Customize the plot as needed

plt.xlabel('X Axis')

plt.ylabel('Y Axis')

plt.title('Bar Plot Example')

# Show the plot

plt.show()

You better believe products like Copilot are using specialized models like this.

But that’s boring, what we really want to know is if we can make our model talk like our favorite TV show.

How to tune friends and influence models

My goal here is to make my LLM talk like a character on the TV show Friends. Why? Because I’m the internet and I get what I want.

I’m using a dataset of Friends scripts from Kaggle. I took inspiration from this walkthrough, which I highly recommend.

There were two ways I can use these data to accomplish the goal above:

(A) Train a model on all dialogue

In this case, I ask the model to predict the next word of all character dialogue. It learns the Friends “tone”, and therefore generate more Friends script-like text. This is similar to the pre-training objective (1) described above.

(B) Train a model on paired exchanges

Here, I’d give the model pairs of lines; exchanges between characters. The model would learn to generate responses in the style of a Friends character. This is similar to the SFT objective (2) described above.

Both of these approaches aim to make a model speak more like a Friends character. But (B), in my view, seems more in line with training it to be a Friends chatbot. Still, I wanted to see how different approaches changes the outcome.

Friends-GPT

A small company you may have heard of, OpenAI, provides a useful set of tools to fine-tune their proprietary LLMs. As part of my work on LLMs in dermatology, I was tasked with doing some fine-tuning experiments with these models. I’ll have a post on that in the next week or so, but for now let’s see how this approach works with our Friends script data.

In this case, we’re looking at training approach B - training on pairs of character dialogue. Check out this notebook to follow along. Note - if you want to run this you’ll need your own OpenAI API key.

I set this up by developing a system prompt that specified this was a conversation between two buddies:

Your name is Friend. You are having a conversation with your close friend Ben. You and Ben are sarcastic and poke fun at one another. But you care about each other and support one another. You will be presented with something Ben said. Respond as Friend.

My input prompt was:

What are we doing tonight?

First, I tried this with the base GPT3.5 model:

Friend: Oh, I thought you were planning a surprise party for me. Should I cancel the inflatable unicorn bouncy castle I ordered?

It’s generally kind of obnoxious, maybe placing too much emphasis on that sarcastic piece. It also sometimes generates that “Friend:” prefix, but it is not consistent. So, it’s definitely not going to be writing any Friends scripts anytime soon.

For fine-tuning we need to do some formatting of the data to play nice with the OpenAI API. This means giving it a system prompt (optional, but a lot of examples use one), an input prompt and an expected output. The input is a line from one character, the output is the next line. I assume these paired lines model the behavior I want the bot to imitate, though there may be some benefit to providing longer conversational context.

For fine-tuning, the documentation says that 50-100 examples should result in improvement. To save time and money, I went with the low end, providing the fine-tuning flow 50 examples. After several epochs of training, I receive my shiny new Friends-GPT.

Provided with the input prompt above, Friends-GPT output:

Well, I kinda had plans to stay in tonight. Throw a few punches, do a little fight clubbin’.

Friends-GPT seems to have caught the “tone” of the Friends script. But it says some pretty odd stuff. And it’s oddly fixated on Ross:

Well, we could go to the coffeehouse and..(notices Ross hasn’t left) or… I could stick my hand in the mashed potatoes again.

Weirdly - “Well,” seems to be its favorite way to begin a reply. It does seem to be pretty common across the script, but I’m not sure if that explains it.

I’d like to experiment further here - I wonder if more data or more conversational context with a modified system prompt might result in better, more sensible output. But at least it sounds a bit more in the style of Friends.

But one issue here is that I don’t really know how the fine-tuning process works. OpenAI keeps its proprietary wall pretty high, which makes it difficult to debug strange outcomes like this one. For the next experiment, I’ll be doing more coding from scratch. Since I (and probably you) don’t work for OpenAI, that means we’ll have to figure out our own compute. And that means we’ll be looking for some optimizations.

I realize this entry is getting a bit long and, honestly, I’m still working on some experiments with the next part. I’m going to end this part here - next time we’ll discuss some model optimizations and how to fine-tune using free resources provided by Kaggle!

What we learned

- Fine-tuning can improve LLM generation for specific use-cases

- OpenAI has useful tools for doing this with their high-powered models, though the results are maybe less exciting (in my current formulation)

More to come!

-

I should not it’s not clear what Llama models are trained on because, contrary to claims otherwise, Llama is not an open source model. ↩

Ben

Ben

New Year, New Blog

New Year, New Blog