In this post, we continue exploring how to “tune” the output of our LLM application to be more…Friends-ly.

This is part 5 of my LLM app series. Technically it’s part 4.5 - a continuation of part 4. In that post, I introduced the importance of fine-tuning and walked through a demo of “instruction tuning” using OpenAI’s APIs.

One issue I identified with the previous demo is that it relies on the closed-source fine-tuning process from OpenAI. We don’t really know what’s happening behind that curtain. But if we want to take matters into our own hands, we’ll need to figure out how to do so without spending OpenAI-level money on compute.

inside of OpenAI HQ, I assume

inside of OpenAI HQ, I assume

Luckily, the AI community is pretty awesome and has developed an array of optimizations that put fine-tuning within reach of even scrappy little hackers like me.

The inevitable maths - Quantization and Low-Rank Adapters (LoRA)

This is going to be a light touch, but I think it’s an important detour to make here. One thing you might be wondering is how I’m going to manage a process of tuning 7 billion parameters. The answer is…I’m not.

Previous eras of fine-tuning involved a paltry few hundred million parameters. But now we’re in the big leagues, even our tiny little Llama 2 model has 7 BILLION parameters. Tuning an entire LLM introduces a slew of new challenges even if you have access to GPUs.

One of the two optimizations I’ll be using is 8-bit quantization of the model parameters. Huggingface has a great article on it that goes into detail here. The light touch explanation is that it represents the individual parameters of the model with lower precision. As you can imagine, lower precision means the model is slightly lower quality, but the compute required to train and do inference is greatly reduced.

One thing to note - the examples we ran through in Ollama and Oobabooga used quantization approaches. For Ollama, that’s one of the reasons we’re able to spin it up on even free-tier Collab CPUs.

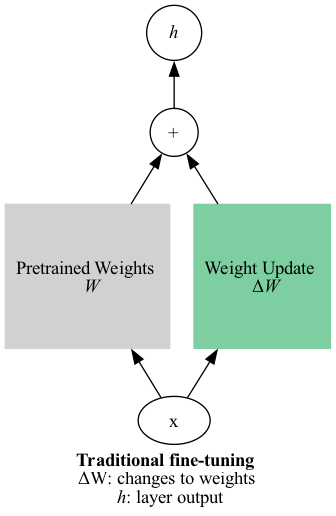

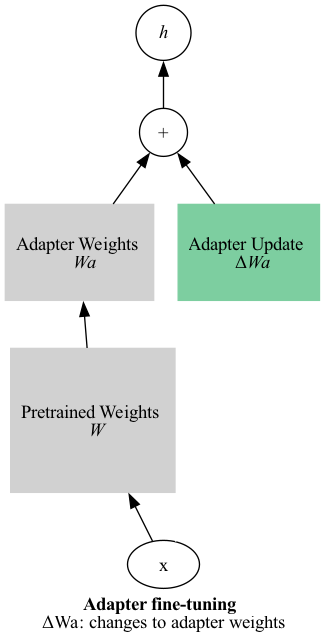

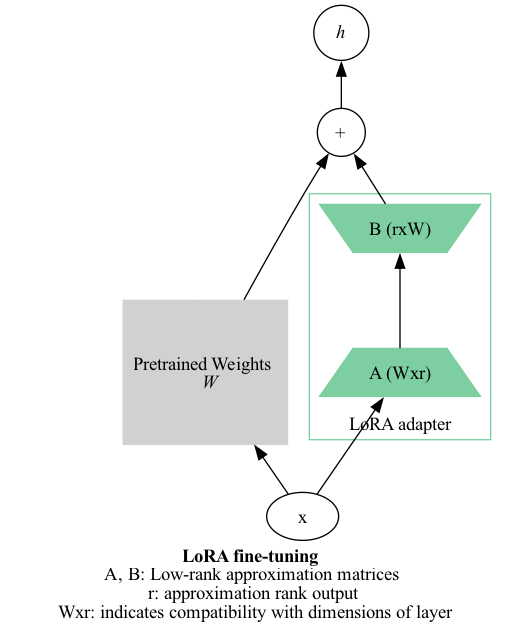

To do the training of the model, I will be using a Low-Rank Adapter (LoRA). Briefly, an “adapter” is a layer that is introduced into the transformer architecture that can be trained along with or instead of the other transformer layers (more detail here). “Instead of” is important here - it means that the other layers can be frozen while just the adapter layers are trained. In traditional fine-tuning, you’d train the entire model, with each step resulting in an update to ALL the parameters. With adapter fine-tuning, you just update the adapter parameters!

Pictures, thousand words, etc:

Note: The “weights” are the parameters updated during training.

“Vanilla” adapters are basically new layers being added to the model. This means they increase the size of the model (number of parameters). Even though training is more efficient, prediction (inference) is slower.

LoRA tries to solve that problem by directly connecting to the existing model parameters. It takes a layer’s input and learns a low-rank approximation of the update for that layer. Instead of that big ΔW matrix, it learns simplified version that contains approximately the same information as the full update. The size of this simplification is governed by a parameter r for the rank of the decomposition.

No new layers - it just adds directly to the layer to which it is attached.1

Basically, the LoRA breaks down what needs to change about the model in simpler terms. Think of it like the Obama anger translator.

Whew - how are we doing? Ready for some code?

The Friends-ly model

For this I switched over to Kaggle notebooks, which is extremely generous with free GPU usage. Follow along here.

I also did this with Modal, because I might have too much time on my hands. No guarantees this will run out of the box for you, it’s still a bit rough around the edges. Check it out.

The first lesson I learned and the one that gave me the most trouble was formatting the data. My goal here was to make the model speak more like a Friends character. To that end, I wanted to train the model similar to how it was pre-trained; on minimally-processed text. Compare that to our Friends-GPT, which was trained on formatted instructions.

But I wasn’t sure what that minimally-processed text should look like! I ended up trying three different datasets:

- Dialogue without the character names

Hey, why can't we use the same toothbrush, but we can use the same soap? - Dialogue WITH the character names

Joey: Hey, why can't we use the same toothbrush, but we can use the same soap? - Chunks of dialogue between characters (with names)

Joey: Hey, why can't we use the same toothbrush, but we can use the same soap?, Chandler: Because soap is soap. It's self-cleaning. Joey: Alright, well next time you take a shower, think about the last thing I wash and the first thing you wash.

Generally, the model did take on the tone of a Friends episode, but depending on whether it saw the character names, it would be more or less likely to generate “script-like” output.

Take a look:

Prompt

Your name is Friend. You are having a conversation with your close friend Ben. You and Ben are sarcastic and poke fun at one another. But you care about each other and support one another. You will be presented with something Ben said. Respond as Friend.

Ben: What should we do tonight?

Base model

Friend: 🤔😓 Oh boy, do we have to? 😅 Can’t we just stay in and watch Netflix? 📺😴

Tuned on lines without names

Friend: I don’t know. What do you want to do? Well, I was thinking of going to the Yellow Cab and having a few beers with Joey. What? You’re going out with Joey?

Tuned on lines with names

Friend: I don’t know. I’m tired. I don’t feel like going out.

Chandler: Hey.

Joey: Hey.

Tuned on chunks of dialogue

Friend: Oh, I don’t know, what are you up for?

Ross: (entering) Hey Ben!

Monica: Hi!

Ross: Hey!

Monica: So, you ready to get married?

Though the output is a bit wonky and it’s difficult to keep it from pulling in all sorts of Friends characters (who all say “Hey!”) - I’d actually call this a success! The model definitely has adopted the Friends script tone. Though, maybe it’s less helpful as a result:

Prompt Tell me about alpacas.

Base model

Alpacas are domesticated animals that are native to South America. They are members of the camel family and are known for their soft, luxurious fleece and gentle nature.

Tuned on chunks of dialogue

Chandler: Oh, theyre just so cute!

Phoebe: Oh, youve seen them?

Chandler: Yeah, Im all about the alpacas.

I also kind of love this one

Chandler: They’re like little ponies.

Chandler: (to Joey) I’m sorry. (Joey is upset) Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to hurt you.

Ending thoughts

Spending a week training a high-powered ML model to sound like a Chandler Bing will get you thinking. Looking at the two experiments I ran here for fine-tuning, I think that maybe the instruction-tuning approach might have been the more relevant one for this use-case.

What I wanted was a chatbot that could talk like a Friends character in conversation. For that purpose, framing the objective around producing Friends-ly speech might be the better approach. This method led to hilarious Friends scripts, but not to very useful conversation.

And, honestly, if making an AI-generated 90s show was my goal…that’s sort of been done.

Play us out, Friends-Llama:

Ben: Hey gang, how do you like this blog post? (shows them the blog post)

Ross: I don’t know, I’m not very tech savvy.

Phoebe: (reading the blog post) Ooh, this is so cool! (reading the comments) Wow, there are so many people who don’t like it.

Notes

The adapter diagrams were inspired/adapted from the ones here

This walkthrough was excellent and inspired a lot of what I ended up doing in this post.

If you’re interested in a deeper dive into these topics, there’s some excellent blog posts on adapters and and LLM training more generally.

Also, I love this talk if you’re interested in the intuition behind matrix approximation.

-

I tried to capture the architecture as best and as simply as I could here. Technically there’s two dimensions; the W-in and the W-out, a particular layer doesn’t necessarily have the same number of input and output dimensions. The idea is that the LoRA doesn’t interrupt that flow - but it shrinks the amount of information that is needed for the update. That’s my understanding, at least. ↩

Ben

Ben

LLM Apps Part 4 - Only the finest tuning

LLM Apps Part 4 - Only the finest tuning