All apologies for the long delay here. Lots of stuff going on including, but not limited to:

- A 3-week journey to China

- The revival of the Boston chapter of PyData

- Various work-related technical fires

But I still have materials from a few more sessions of MIT’s Statistical Learning class. So I’m planning on going through those and then moving on to some exciting NLP-related material.

This session focuses on the idea of kernels and how they can be used to open up opportunities for a variety of models.

Note: From this point on, the slides link may have slightly out of date materials (from 2018), but most of the information matches up.

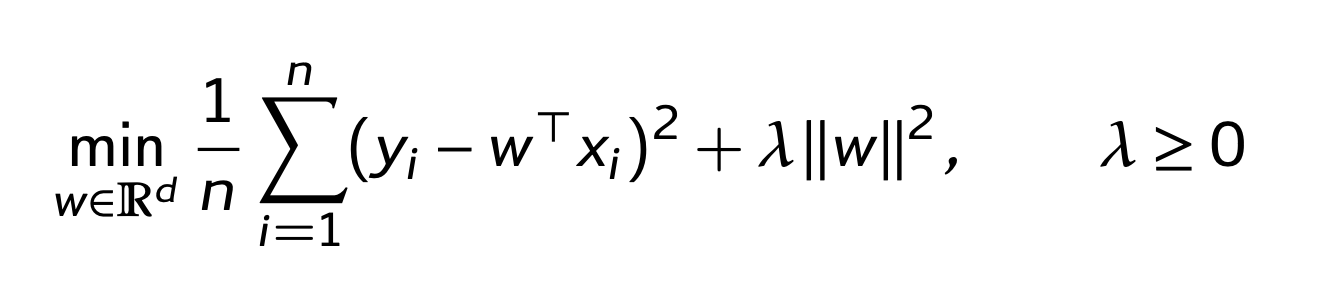

As a refresher, here is the Expected Risk Minimization (ERM) for regularized least squares:

Again, the minimizer for \(w\):

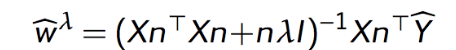

This notation is a bit different from what we had in the last lecture. I did a bit of searching and I’m not sure why these \(n\)’s are here, but they continue into the next formulas, so I am keeping them.

Anyway, this can be rewritten using the representer theorem

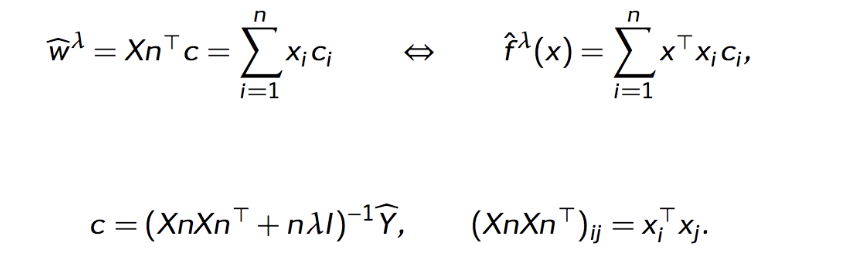

Why is this rewrite of f(x) important? Because it shows that the solution really only depends on the inner product of x. And why does that matter? Because you could use many types of transformations of x and you’d just have to solve in terms of those transformed vectors rather than the original vectors. This includes nonlinear transformations:

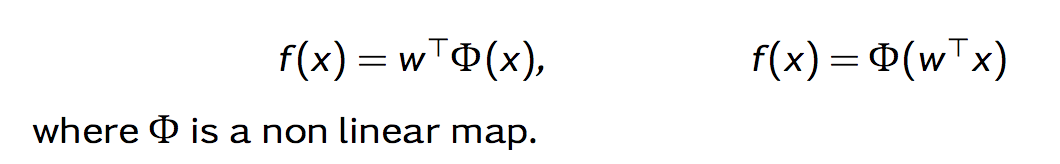

The nonlinear formulation of f(x) can be written as:

The formulation on the left is a mapping of each x value to another value in a reprojected space. Typically, that space is higher-dimensional as it enables you to use a greater variety of functions to fit the data (rather than just a line).

The inner product of these transformed vectors is referred to the kernel. So we don’t actually need to use the individual points themselves, but the inner product of the points. So long as we know that value, we don’t really need to worry about the data points themselves or even, really, the transformation. This is referred to as the “kernel trick” and I’m drastically oversimplifying it here. There’s a clearer description of the intuition here and a more math-y explanation here.

The upshot here is basically by using this “kernel trick”, we are able to transform data our data in ways that open up opportunities for better models. What sorts of better models, you ask? Well, stay tuned.

Ben

Ben