All apologies for taking so long to get back to this, lots of development in life has kind of derailed my routines. But I want to keep to a schedule of updating on a weekly basis. My thinking is I may leave off on this Deep Learning course as I’m finding the material, while super fascinating, a bit far away from what I’m working on. And there’s a bunch of material coming out on Natural Language Processing I’ve been looking to dig into.

So here I’ll do my last summary from the CS230 lectures (for now) and next time we’ll go through something more NLP. Sound good? Great!

This lecture is a bit different. We hear from a practitioner in the field, particularly one working to apply AI technology in healthcare. Stanford PhD Candidate Pranav Rajpurkar takes us through some healthcare applications he’s worked on and Kian Katanforoosh picks up with a more in-depth technical dive. Again, all materials below are from the lecture unless otherwise noted.

Pranav starts off with some of the high-level questions asked of AI in the healthcare field: What happened? (Descriptive) Why did it happen? (Diagnostic) What will happen? (Predictive) What should we do? (Prescriptive)

Pranav makes the argument that AI has a lot to offer in each of these areas and uses this as a launching point to talk about some of his recent work. The three examples he goes into use three different types of data; one-dimensional data (i.e. ECG data), two-dimensional data (i.e. Chest X-Ray images) and three-dimensional data (i.e. Knee imaging).

The ECG project aimed to detect arrythmias (i.e. irregular beating of the heart). Though ECG technology is pretty advanced, the most accurate pieces of technology are difficult for a patient to carry around. Though there are portable versions, they are a bit less accurate and it’s generally hard for a doctor to go through, minute by minute, a long period of ECG recording.

Where AI can come in here is by being able to scan through large amounts of ECG data and label where arrythmias (or other patterns) are happening. This is done by breaking the ECG signal into segments and training the AI to detect what is happening.

Pranav goes through a brief overview of the architecture, which involved Convolutional layers and Residual Networks (ResNet), a structure that allows information to be shared between layers at different depths. I’m not too familiar with this architecture and he touches on it only briefly, so let’s just suffice to say it was a method that accounted for the inherent complexity in finding patterns in these data. In a test versus the clinician labels, the model performed better, though there were weakness in certain areas of detectin.

The two-dimensional example focused on analyzing Chest X-rays to detect pneumonia. Typically, experts will look at these X-rays and identify areas of the lung with different density, which may indicate fluid filling the aveoli. This task seems to lend itself to the advanced image analysis capabilities of AI. Pranav and his group used a Convolutional Neural Network with a DenseNet architecture. DenseNet is similar to ResNet, except instead of there being one avenue for sharing information between layers, every layer is connected to every other layer.

This DenseNet/ResNet difference is super fascinating, but I don’t really understand what decisions go into choosing one or the other (or neither!). If anyone has a good explanation here, I’d be eager to hear it.

A challenge with the dataset used here is that there wasn’t a ground truth. Instead, a set of radiologists had analyzed the images and made notes about what conditions they saw. None of these labels are definitively “ground truth”, as it’s possible the radiologists could be mistaken. Instead of trying to assess the accuracy of the model, Pranav’s group looked at the inter-rater agreement between the experts and the NN. The results indicated that the NN had higher agreement with the other radiologists than any single radiologist.

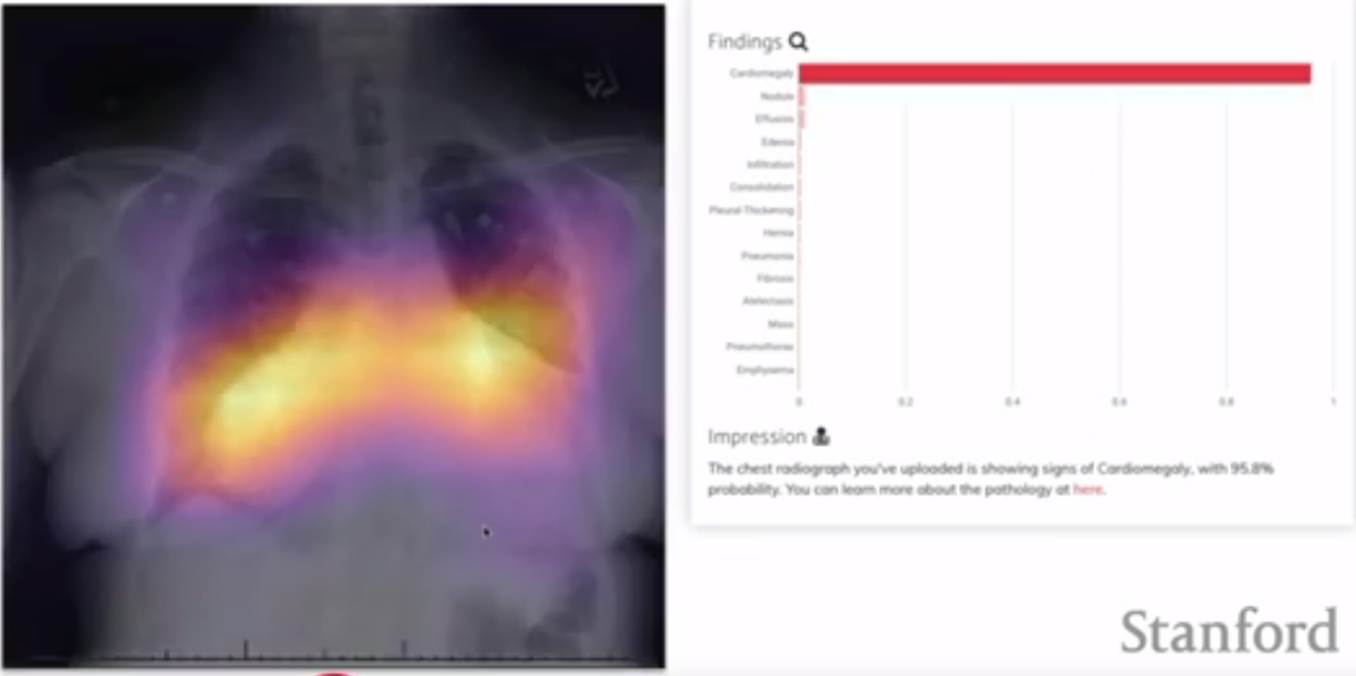

A nice feature that one can extract from a model like this one is a map over the image of where the NN is getting its information. If the NN, for example, determines an image is likely to be one of a patient with pneumonia, a “class activation map” will highlight which pixels the NN used to make its decision. This might be useful in highlighting abnormalities in an image.

The final example Pranav dives into is a three-dimensional dataset of Knee MRIs. To diagnose issues with the knee, radiologists typically examine knee images taken from different orientations. An AI model would need to also examine these different orientations in order to diagnose. Further, a knee may have any number of abnormalities (e.g. ACL issue, Meniscus issue).

Pranav and his group addressed these complexity by training 9 CNNs, one for each orientation-abnormality pair. They combined the 3 CNNs for each abnormality by using a logistic regression. The model did reasonably well and the CNNs were able to identify areas of the image likely to indicate abnormality (similar to the above).

From here, Kian takes over to go in depth into another image-based health application for AI; segmenting cells from an image of multiple cells. He does the familiar breakdown of goals, data and architecture:

- Goal: Identify which parts of an image correspond to a cell

- Data: 100k images from three microscopes

- Microscope C is the target microscope, so need to include C images in train, dev and test dataset

- Since there are so many images, probably can use a split 90-5-5 train-dev-test

- Architecture: CNN

- Activation: Sigmoid

- Loss: Cross-entropy of predicted cell boundaries summed over all pixel values

Though there is a lot of data available, there’s likely going to be a need to augment the dataset. This “data augmentation” is common with image dataset and Kian proposes solutions like rotation, zooming, blur and stretch. However, he cautions against always using these techniques as they can harm a model that is unlikely to see the augmentation you’ve used. For example, in face recognition, turning a face upside-down doesn’t make too much sense, as the model will likely not need to classify upside-down faces.

Kian explains here that just running your CNN on the cells and trying to predict where the cells are is not going to be enough. He suggests, rather than starting from scratch with an untrained CNN, you use a CNN already trained on something like skin-disease classification. In this case, the model has already learned some important features, likely in the earlier layers. So to make the best use out of this pre-trained model, you’d likely specify some layers to freeze (i.e. not train) and some layers to train with your new dataset.

“But wait!”, Kian exclaims. We can do better. Our first model is just trying to predict where the boundaries are, which is a pretty difficult task. Instead, what if we asked the model to predict which pixels were cell, which pixels were not cell and which pixels were boundary. In this case, we can adjust our loss for the different classes to make the model prioritize correct prediction of boundary and learn some features related to cells/not cells rather than just deciding boundary/not boundary.

This is a bit of a simplification, there was a lot Kian covered in this example and definitely would require diving in to the papers themselves to get a real handle on the advantages of the different approaches.

We’ll leave it there, then. Next time, we’ll dive into some exciting NLP-related talks and topics.

Ben

Ben