This is an update of some materials from my Harvard NLP course. I focused here on three methods for representation of text data that are simple, quick and transparent. This is part of some materials I’m putting together for Pluralsight, more on that in the future.

I’ve been cranking away on my upcoming ODSC tutorial, but I wanted to put out something in the meantime. Working on this also allowed me to reflect on the utility of these different approaches and I’ll have some thoughts there.

Check out the github repository to access the slides and the notebook. All data is public and the notebook is quick to run on a basic Colab instance.

I propose my own idea of the purpose of NLP; responding effectively to informative representations of text. What this means is that any NLP system should have two basic components:

1) Generating a representation of text data 2) Utilizing that representation for an application

What is a representation? It’s kind of an interesting question and one I’ve been researching. Here, it’s translating text into some format that can be used effectively by the system. That can be as simple as a count of words or just some engineered features (e.g. string length). Probably you want to be able to capture something specific to the individual document being processed, which is where things get interesting.

Count vectors

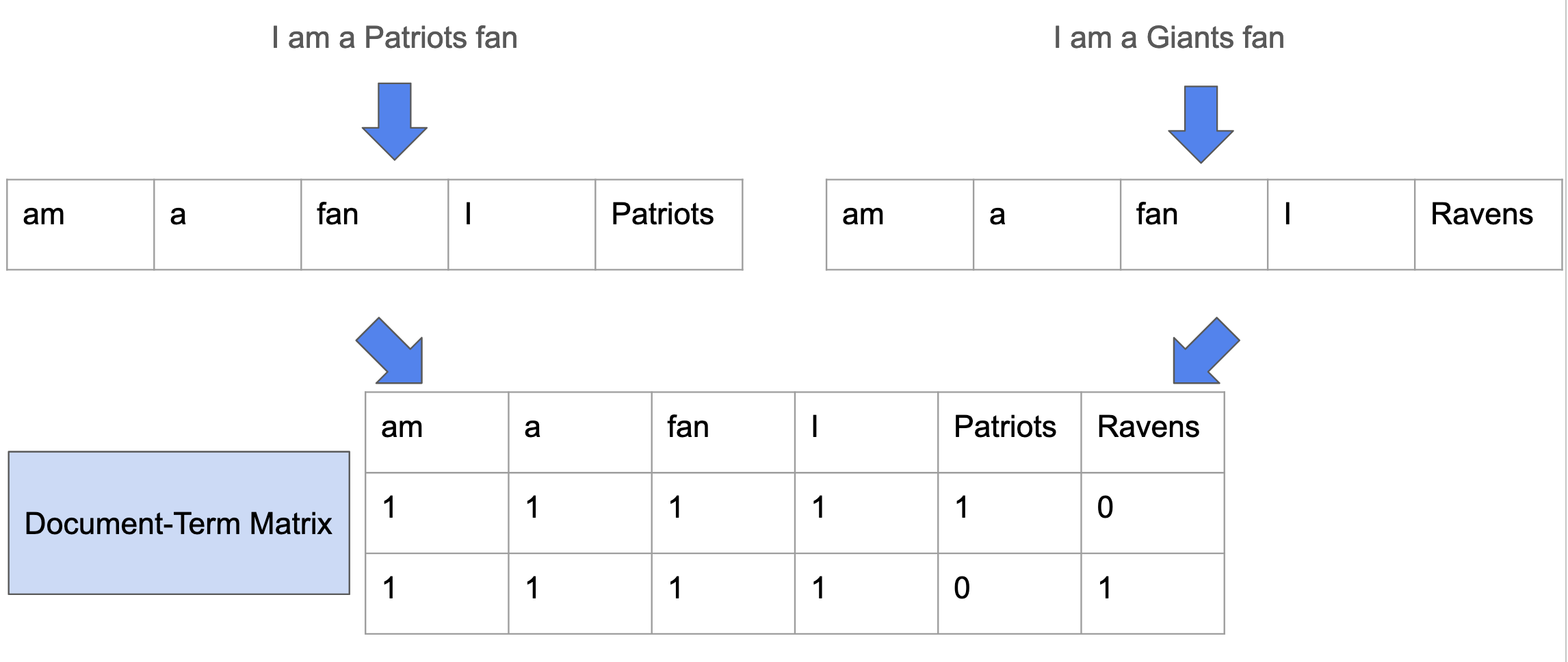

When we talk about vectors in data science, we’re usually talking about a collection of numbers (though it means something specific in mathematics). In this context, we’re talking about the counts of words across a vocabulary.

The example in the slides takes two documents and turns them into a pair of count vectors. A “document-term matrix”. Each row in the matrix is a document and each column is the number of times a term appears. Quick note: The words term, word and token each have slightly different meanings, but to some extent they’re interchangeable in these examples.

This alone gives you some interesting information about your documents. There’s been many times where just looking at term frequencies I’ve understood that there may be code, html or a mixture of languages in the corpus. Even though a lot of the modern technology use more elaborate tokenization strategies, this approach is still a useful representation. And one you can do with ZERO dependencies! (see collections.Counter)

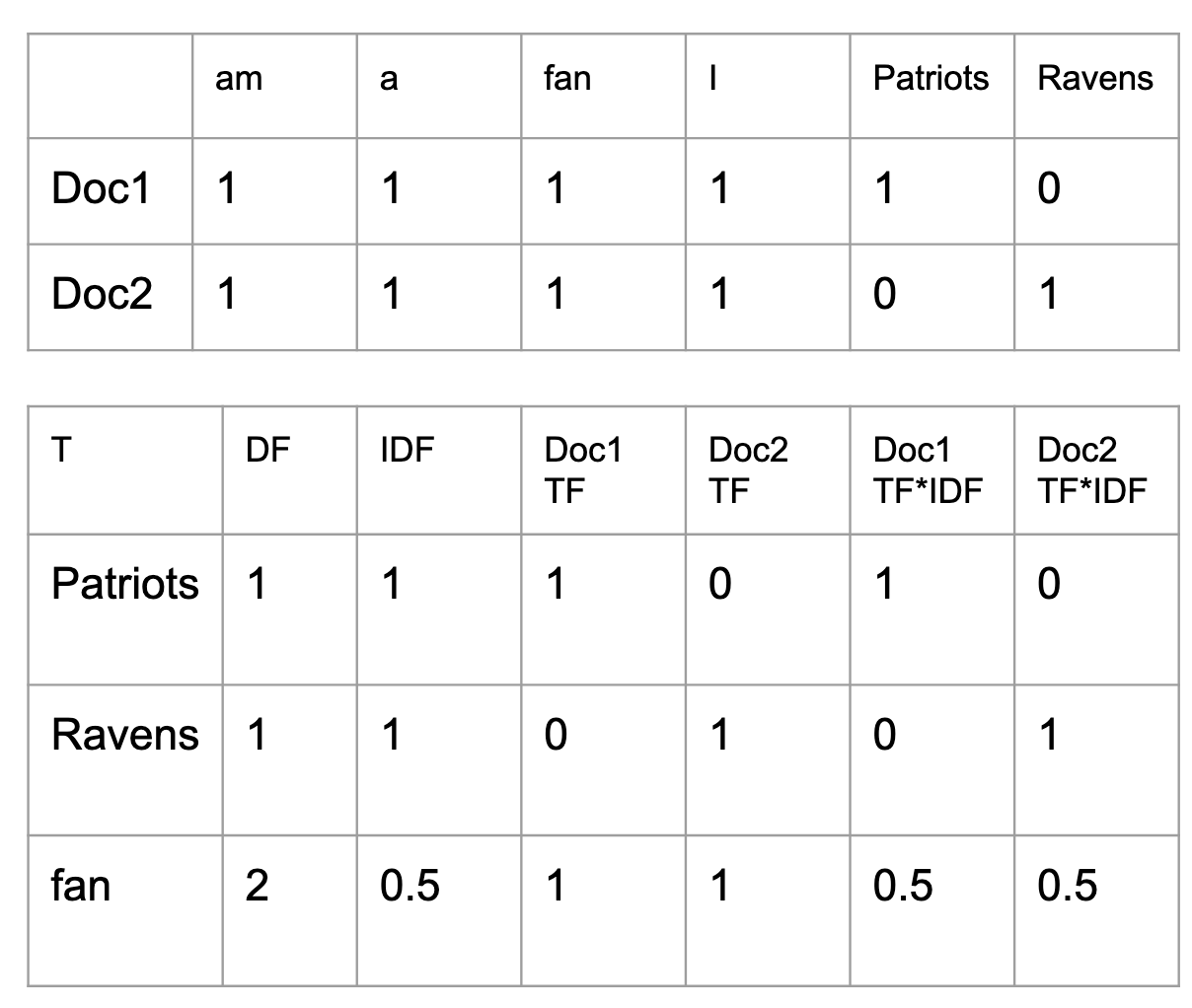

I next move on to a stategy for reducing the “noise” inherent in this representation by creating a weighting scheme for word counts.

Weighted count vectors

The method I cover here is called Term Frequency - Inverse Document Frequency, which sounds intimidating, but it’s really just using a simple heuristic for weighting the word counts. The heuristic is the inverse of the number of times a word appears in a collection of documents (corpus). The idea is that common words like “the” will be downweighted (high document frequency) and words more characteristic of a particular document (low document frequency) will be upweighted.

What’s interesting here is that using these vectors for sentiment analysis doesn’t improve performance over raw word counts. My interpretation of that is that there’s nothing about a word being relevant to a particular document that suggests it will be relevant to the document’s expression of sentiment. It may, however, create a more “descriptive” representation of that document’s content. I demonstrate that by showing the similarity between TFIDF vectors in positive reviews and negative reviews is lower than the similarity with count vectors. It supports my interpretation - but I’m not really convinced of the value of IDF-weighting here.

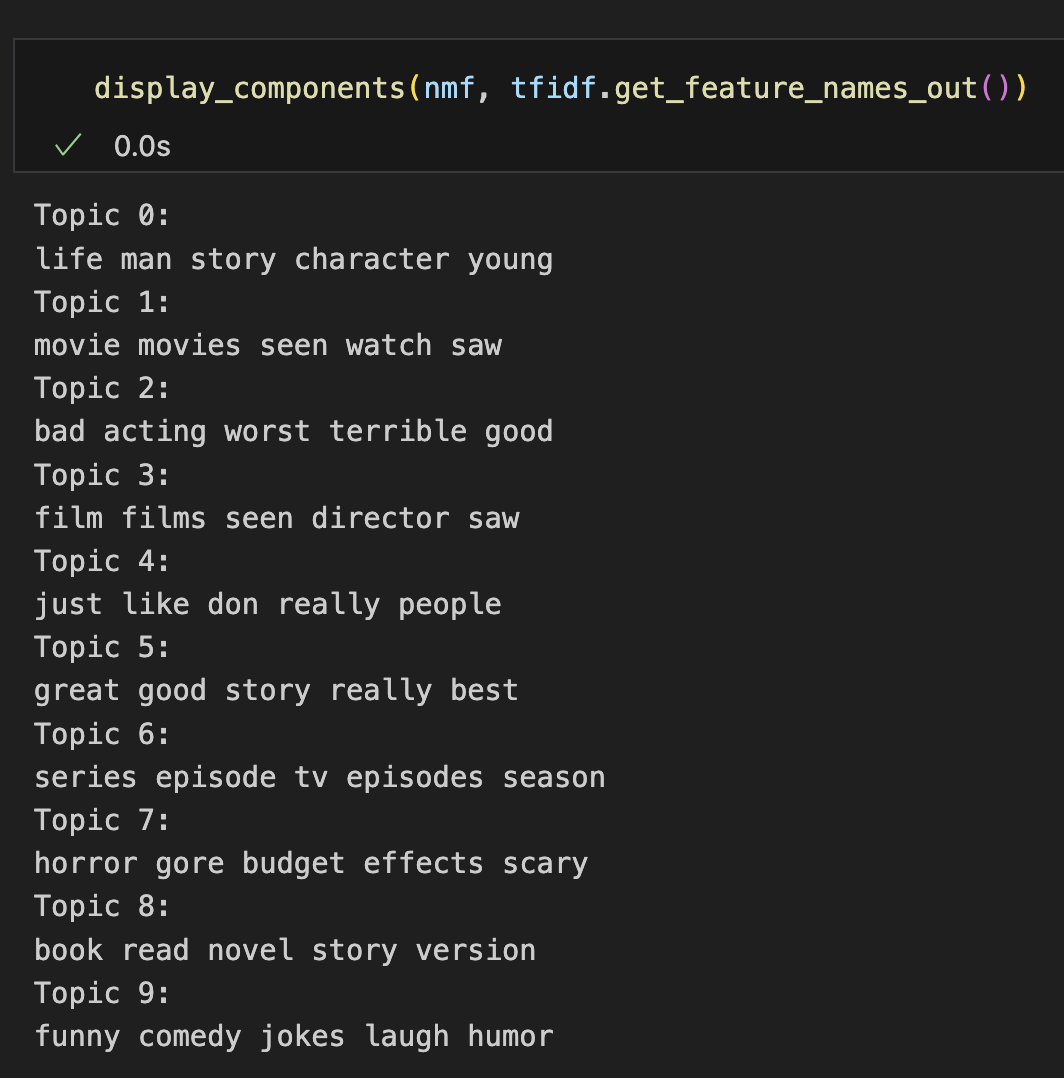

Topic models

Topic models were all the rage before the machines took over. They were simple to set up, easy to interpret and had a nice, clean intuition. But, as with any unsupervised approach, interpretation is a little bit art and a lot of hand-waving.

The main idea of topic models is that a document is composed of topics which, in turn, are composed of words. Each word in the vocabulary has some relevance (“loading”) on each topic. Each topic describes each document to some degree. Looking at some of the top loading words across documents is pretty easy to interpret:

Unsurprisingly, these make pretty terrible features for sentiment prediction. They’re better than just curating a set of words (e.g. “bad”, “good”), as they do contain some information about the documents themselves.

Some closing thoughts

I had heard in a presentation that these methods are the “stone age” of NLP and that we’re currently in a “Renaissance”. I’m not sure if the speaker meant it this way, but it sounds fairly dismissive of a set of techniques that are, at the very least, transparent. And at best, these methods are still workhorses. If you can predict sentiment with 80% accuracy using standard methods - what would be involved in getting to 85%? At minimum, I always will throw these techniques at a dataset because they will at least give me something to compare against.

Maybe “stone age” is actually the right term. I mean, we still use bricks, after all.

Ben

Ben

EU's AI Act - What it is, what it means

EU's AI Act - What it is, what it means