On Wednesday, European Union leaders approved the AI Act, which proposes a “risk categorization” framework for the use of AI. Some uses will be banned all together, while others will be highly regulated. The EU has been working on this framework for years, first proposing it in 2020 in their White Paper on Artificial Intelligence. Since then, the framework has been formalized and adapted to address fresh concerns about generative AI.

Incidentally, I have been digging into AI policy in order give myself a better sense of what’s coming down the pipe. This big news gives me an excuse to publish some of my explorations. I’m particularly interested in how the AI Act system works and how it might influence regulation here in the US. We all remember how GDPR buried us in legal disclaimer pop ups. Once again the EU is leading the way on regulating a complex, fast-expanding industry. So what does the regulation look like?

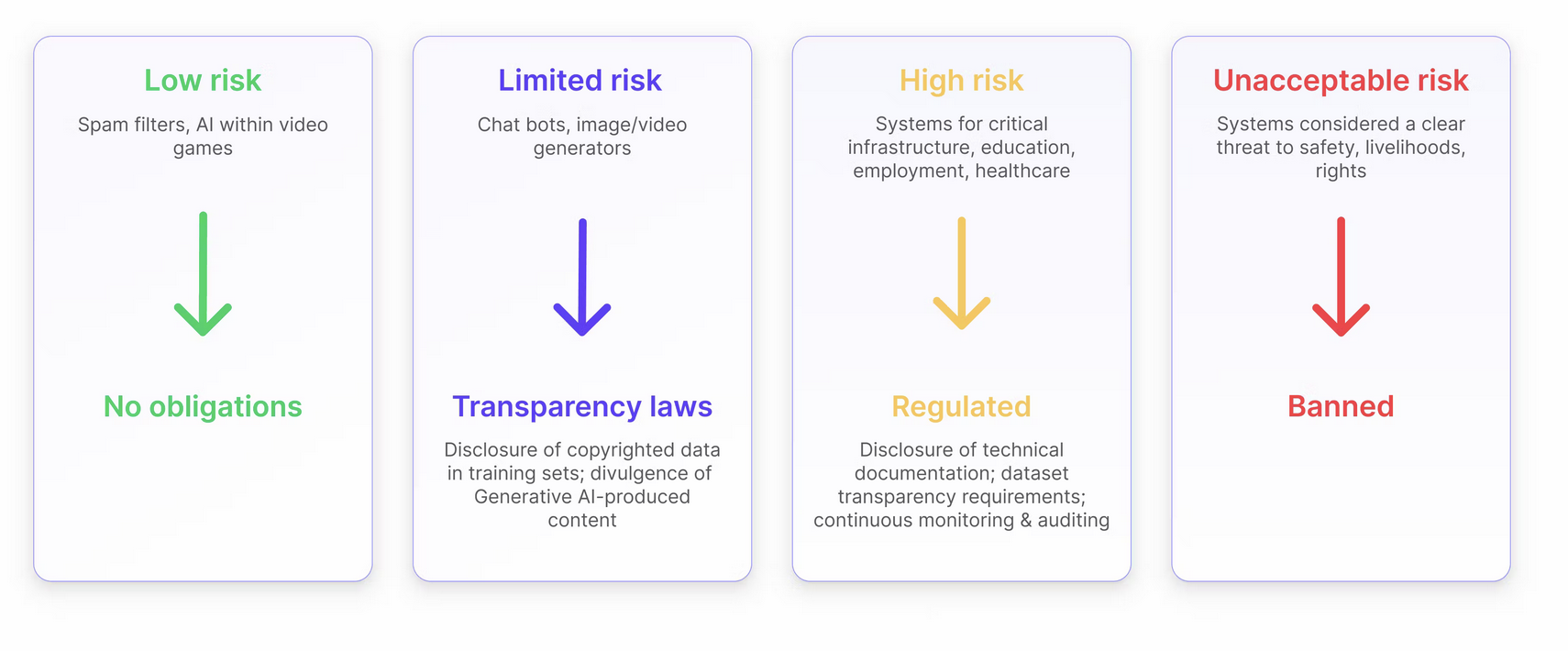

AI risk classification

This visual from Encord breaks down the classification system. I’ll describe in more detail what each category means.

Unacceptable risk: Outright banned

The motivating idea here is that application in this category pose a clear risk to fundamental rights. This includes systems that manipulate users (called “dark pattern AI”) or exploit vulnerable groups. Since many algorithms impact what promotions/prices a user might see, one could imagine this potentially having broad implications.

Additionally, “social scoring” applications will be banned. This is likely a response to alarm about systems like China’s social credit system. But this also ties back to the previous point; AI applications that potentially exploit vulnerable groups will be banned.

Another application banned under this regulation is technology assessing the risk of an individual committing a crime. This seems like it would cover technology like the much-maligned COMPAS algorithm, which predicted recidivism risk. Interestingly, though, the language of the Act makes allowances for these technologies if they “augment human judgement”. This seems like a potential loophole to me as it is unlikely the technology would make decisions on its own. Would it be enough to just have a human in the loop to move this from “unacceptable” to “high risk”?

There are a few of these exceptions for law enforcement purposes. One issue that was fiercely debated in the run up to the Act approval is the use of biometrics for identification (e.g. facial recognition). These are banned as posing “unacceptable risk”, except in cases of serious crimes (e.g. terrorism).

High risk: Extensive reporting requirements

High risk applications are permitted, but subject to strict regulation. An application is high risk if it is part of a product covered under existing EU laws (e.g. autonomous vehicles, medical devices) or it is applied in a sensitive setting (e.g. critical infrastructure, law enforcement). These categories seem to have some amount of overlap, as is the case with medical devices. Below I link to more detailed summaries of the Act, which gives detailed lists.

The Act gives specifics about the framework of requirements established for providers of these high risk applications. They must set up risk management systems which cover the entire lifecycle of the AI application along with data governance and monitoring processes. The idea is that systems must tracked against metrics of performance, consistency and security. Deviations from these expectations would be subject to incident reporting requirements.

There are also requirements for providers to allow deployers to implement human oversight. The language of the Act seems to point to system “transparency”, describing “measures to facilitate the interpretation of the outputs of the AI system by the deployers”. Interpretability is a difficult nut to crack from both a methodological and IP perspective. I’m very interested to see how this requirement is handled by application developers.

Limited and Minimal risk: Transparency requirements

For limited risk systems like chatbots, the focus is on transparency. Specifically, a user needs to be informed that they are interacting with an automated system. This covers AI-generated content more generally; it needs to notify viewers that the content has been generated. Again - I’m interested to see how this shakes out. Does this mean all my Midjourney blog images will have disclaimers on them?

For minimal risk applications like gaming and spam filtering, there are no specific reporting requirements. That means no requirements for transparency, as is required for limtied risk. I wonder where the line is between limited risk AI-generated content and minimal risk content.

Can I keep my ChatGPT?

This framework was first established in 2020, back in the olden times where people sat in caves striking word vectors together to make sparks. Needless to say, things have changed a bit. Generative AI models are being slotted into all kinds of systems. To some extent these applications are already covered in the regulation; if a medical device uses gen AI, it is regulated as high risk because it is a medical devicce.

However, what about other applications of gen AI that are not covered? The AI Act specifically calls out products like ChatGPT as “General Purpose AI Models”. This is in reference to their usage for purposes other than that for which they were designed1. Companies that provide these models will need to make available a detailed summary of the training data. OpenAI has cited numerous justifications for closed-sourcing its products. Regulation here, it seems to me, might begin to pry open some of their black boxes.2

Additionally, companies will need to implement a risk assessment framework similar to what is required for high risk applications. One key difference is that their assessment must include environmental impact; companies will need to disclose how much energy their models use.

What’s next?

The AI Act has a few more steps in the approval process, but is on track to be made into law in May or June. That means by the end of the year, member countries must put in their own bans on restricted uses of AI. By mid-2026 - we can expect the regulatory system will be active and enforcing the requirements detailed here. Fines for violations are steep enough to put even major companies on notice.

This means a scramble by companies to do their own due diligence and understand where they fit in this landscape. EU member countries themselves will be scrambling to set up the systems to support enforcement. These local systems will need to connect up to the larger European AI Office.

Yeah, but what about US?

There is increasing attention on the risks posed by AI in the US. I’m planning a longer blog post on this, but we already were given a bit of a preview of US thinking in October with Biden’s Executive Order on AI. The language is fairly soft here, but it does call attention to the key principles that may spin into a larger piece of legislation like what has been proposed in the Algorithmic Accountability Act.

It should be no surprise for anyone familiar with policymaking in the US that a lot of the burden of regulation has fallen on individual states. The result is a patchwork of regulation. It may be that the AI Act provides a model to which both states and federal regulation can refer.

Useful resources

- I really liked this brief AP article on the AI Act

- EU summary of AI Act

- Useful AI Act Explorer tool

- Interesting article on implications for developers

- Really interesting toolkit and resources on Responsible AI

-

I can’t find the Tweet right now, but someone had made the point that arguably these gen AI models weren’t made for any purpose. And that makes them extremely difficult to control and regulate. ↩

-

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has actually expressed concerns about OpenAI’s future in the EU ↩

Ben

Ben

LLM Apps Part 7 - Looking ahead

LLM Apps Part 7 - Looking ahead